David Ross McCord: A lifetime devoted to preserving memory

Learn more about the McCord Museum's founder and the building of his collection.

October 12, 2021

David Ross McCord (1844-1930) devoted his whole life to creating a museum. However, the mission he set himself had disastrous consequences on his finances and personal relationships, as well as his mental health.

We know very little about McCord’s childhood. His father, John Samuel McCord (1801-1865), a member of Montreal’s elite, was a landowner and judge in the Circuit Court of Montreal and Superior Court of Quebec. An amateur scientist with a passion for meteorology and botany, he instilled a love for scientific practice in his son.

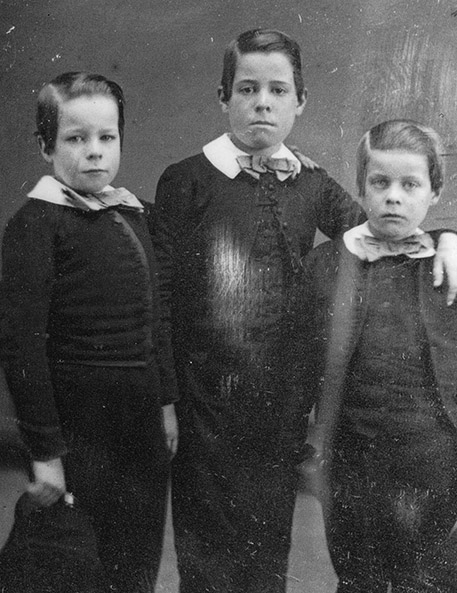

David Ross McCord’s mother, Anne Ross (1807-1870), studied with artist James Duncan (1806-1881) and was an accomplished watercolourist. An avid collector1, she encouraged her son’s interests in art and history. The couple lived with their six children (Eleanor Elizabeth, Jane Catherine, John Davidson, David Ross, Robert Arthur and Anne) in Temple Grove, a Greek Revival-style residence that John Samuel had built on the southwest slopes of Mount Royal. Here, in a place full of memories, surrounded by familiar objects, McCord spent his life assembling his collection.

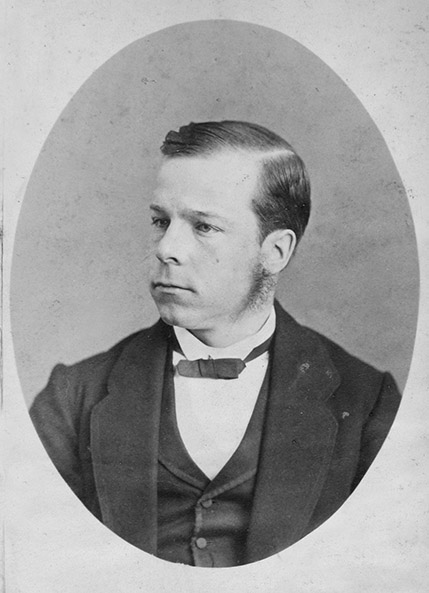

McCord received a classical education at the High School of Montreal, studying French at his father’s urging. He then attended McGill University, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1863, followed by a Master of Arts and Bachelor of Civil Law in 1867. After clerking with the firm of Leblanc, Cassidy and Leblanc, he was called to the Bar in 1868 and opened his own law practice on Notre Dame Street.

However, young McCord’s life took an unexpected turn. His father died in 1865 and his older brother succumbed the following year. This made 23-year-old David Ross McCord the family patriarch, a role for which he was ill prepared2. Aware of the responsibility attached to this duty and undoubtedly affected by the two deaths, McCord became obsessed with the need to perpetuate the family name and, further, keep it alive in the collective memory of Canada. The idea of social recognition took on even greater importance because neither McCord nor his siblings had any children3. Realizing that he would be the last of the McCords, he looked for a way to immortalize4 his family line by founding a museum that would bear its name.

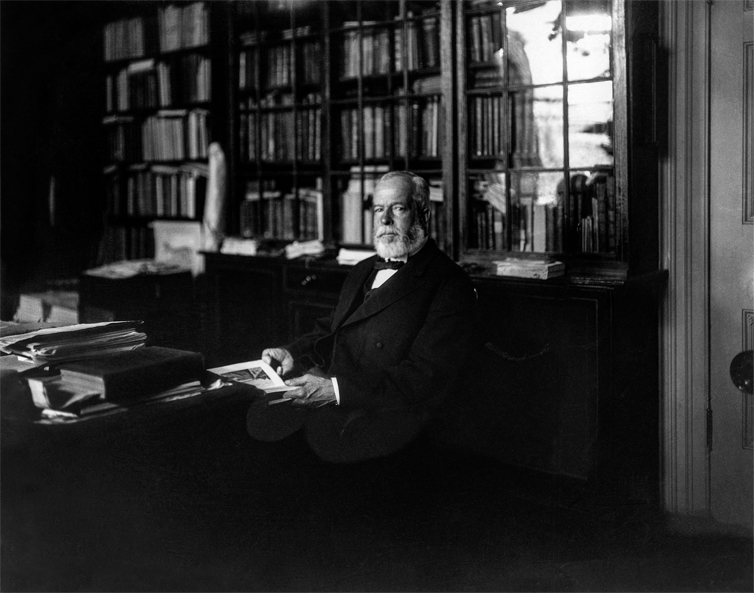

McCord gave up his law practice around 1895, devoting all his time to expanding his collection. Ironically, the McCord Museum would not have existed if he had not taken control of his parents’ legacy, at the expense of his sisters and brother5. An ardent imperialist, McCord considered his museum project a divine mission6, casting himself as a devoted son and loyal servant of Canada, chosen by God to save objects from the British Empire and thus preserve and celebrate Canadian history and ensure national unity.

David Ross McCord’s perspective on history was personal, subjective and rooted in colonial ideologies. The Indigenous objects he collected were stripped of their meaning and those who created them were not recognized as experts. An eccentric man, obsessed with his museum, McCord would do absolutely anything for his collection, confessing in one of his notebooks that he had even resorted to theft7.

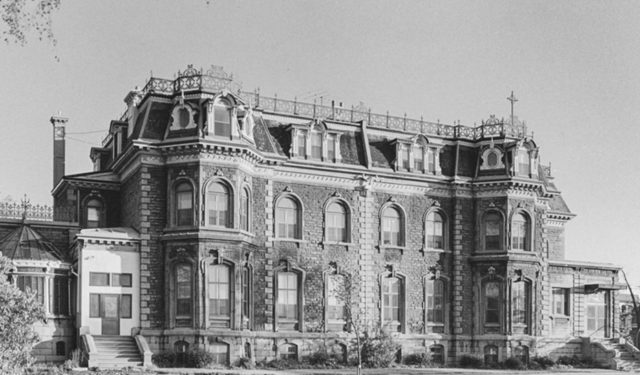

In 1909, David Ross McCord was in serious debt and his health was faltering8. He began searching for a new space for his collection—an institution, preferably a school, willing to provide him with a building and the funds needed to maintain it. He turned to his alma mater, McGill University, and began negotiations that culminated in him donating his collection to the institution in 1919.

The McCord National Museum opened its doors on October 13, 1921. Paradoxically, the inauguration of the museum marked the end of its founder’s activities. Ten months after the McCord opened, afflicted with atherosclerosis and vascular dementia that led him to try to kill his wife on two occasions, David Ross McCord was committed to a psychiatric institution9 where he lived to the end of his days. He died on April 12, 1930.

“What we have loved, others will love, and we will teach them how.”10

David Ross McCord envisioned inscribing this quote from poet William Wordsworth on a wall in the museum bearing his name. Although he did not write it himself, this sentiment strikingly captures the philosophy of a man who devoted his life to transmitting and raising public awareness of his passion for history.

NOTES

1. Pamela J. Miller, “When There Is No Vision, the People Perish. The McCord Family Papers 1766-1945,” Fontanus, Vol. 3, 1990, p. 26.

2. “A sad day for us, for with every month we realize more fully the depth of our affliction. We are, so to speak, without a head for I am, of course, too young to hope to occupy my father’s place for many years to come, [if] I ever shall.” MCFP, file #1812, D. R. McCord to Mrs. Langdon Cheves, July 1, 1867.

3. In 1878, he married Letitia Caroline Chambers, matron at the Montreal Smallpox Hospital.

4. Ordering a family tombstone in 1914, he had the Latin epitaph Resurgam (“I shall rise again”) engraved on it, a reference to this fear of extinction.

5. As executor of his parents’ will, he controlled his siblings’ inheritance. Younger brother Robert Arthur died penniless despite taking David Ross to court. To cover the costs associated with his collection, McCord mortgaged the family home and borrowed thousands of dollars from his sisters. Infuriated, his sister Anne cut him out of her will.

6. In a letter addressed to Mrs. Austin-Leigh of London, he compared himself to Jacob: “The Lord also found me in a desert land, very desert historically, in the sense that no one had thought of saving the landmarks. He led me about. He directed my steps…listened to my voice ‘crying in the wilderness,’ with the happy result that more than a solid foundation has been made for a museum.” MCFP, file #5007, D. R. McCord to Mrs. Austin-Leigh, September 4, 1919.

7. “I stole what I could not buy. Arrogance.” Cited in Kathryn Nancy Harvey, David Ross McCord (1844-1930): Imagining a Self, Imagining a Nation (PhD dissertation, McGill University, 2006), p. 224.

8. McCord had suffered a stroke in 1908.

9. The Homewood Sanitarium in Guelph, Ontario.

10. MCFP, file #2026, Historical Note Book, vol. 3. This quote is taken from William Wordsworth’s The Prelude, book 14, lines 444-445.