Article

| 2 min

An Unforgiving Art

Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio or Controlling One’s Image in the 19th Century (Part 4 of 6).

Sarah Parsons, Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Vanessa Nicholas, PhD, Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Katy Lemay, Illustrator

June 28, 2022

We cannot know for certain what motivated all the concerns about images made at Notman’s studio. Social constructs around privacy, gender, commerce, class, and bodily autonomy seem to have guided a number of the restrictions. However, it is reasonable to conclude that Victorians were as driven by the occasional bout of vanity as the rest of us and that this feeling would shape efforts to limit the circulation of both unflattering and flattering images.

FATAL TO WOMEN

In the late 1850s, the English poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning called photography “fatal to women” because it produced likenesses that were needlessly rigid, making subjects look irritated and ugly. The stakes of visual representation have always been high for women, but photography intensified and broadened expectations to perform femininity in a socially acceptable way.

Before photography, the options for portraits were more forgiving. Silhouettes were inexpensive outlines of one’s profile filled in with black ink and conveyed little in the way of details. Painted portraits were accessible to a significantly smaller section of the population and tended to be generously rendered to flatter the sitter.

MRS. TERRETT

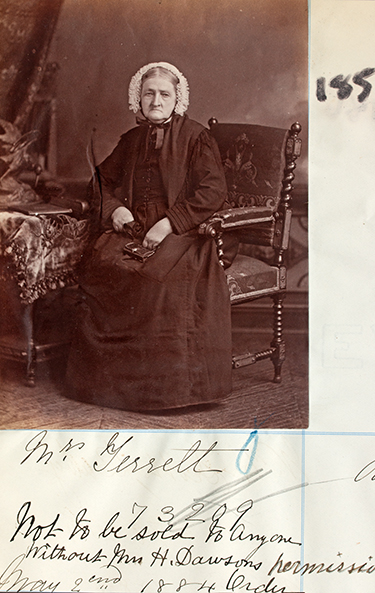

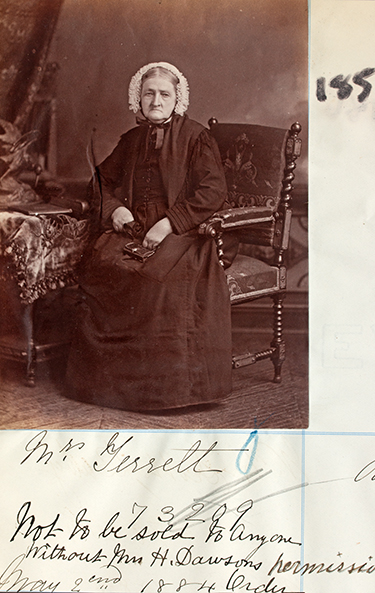

Barrett Browning’s warning seems prescient for Mrs. Terrett who sat for Notman in 1884. As a young widow with five children, Henrietta Terrett emigrated from Ireland to make a life for her family in Montreal. Despite her accomplishments, the elderly woman captured by Notman looks completely forlorn.

William Notman, Mrs. Terrett, 1884. II-73209.1, McCord Museum

Restriction: Not to be sold to anyone without Mrs. H. Dawson’s permission

Mrs. Terrett might have been a contented soul simply displeased that her daughter, Mrs. Dawson, had commissioned the portrait, but we do know that her daughter carefully restricted circulation of the image. Perhaps driven by vanity on her mother’s behalf, the daughter ordered the studio not to sell the matriarch’s portrait to anyone without Mrs. Dawson’s permission. This directive would seem to include not selling the image to Terrett’s other children, since families were the most likely to purchase copies for their own albums and domestic decoration.

The series Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

About the authors and the illustrator

Sarah Parsons, Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Sarah Parsons is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University, Toronto. She is the author of several texts on Notman including

William Notman: Life & Work (The Art Canada Institute, 2014) and “Notman’s Studio as a Space for Performance,” in Hélène Samson and Suzanne Sauvage ed.,

Notman: Visionary Photographer (McCord Museum, 2016). These articles are part of

Feeling Exposed: Photography, Privacy, and Visibility in Nineteenth Century North America, a multiyear project supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Sarah Parsons is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University, Toronto. She is the author of several texts on Notman including

William Notman: Life & Work (The Art Canada Institute, 2014) and “Notman’s Studio as a Space for Performance,” in Hélène Samson and Suzanne Sauvage ed.,

Notman: Visionary Photographer (McCord Museum, 2016). These articles are part of

Feeling Exposed: Photography, Privacy, and Visibility in Nineteenth Century North America, a multiyear project supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Vanessa Nicholas, PhD, Department of Visual Art and Art History, York University

Vanessa Nicholas recently completed a PhD in the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University. Her research interest is in nineteenth century Canadian visual and material culture, and her doctoral dissertation is a close study of the floral embroideries found on three historical Canadian quilts. She is a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar, and she was the 2019 Isabel Bader Fellow in Textile Conservation and Research at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre.

Vanessa Nicholas recently completed a PhD in the Department of Visual Art and Art History at York University. Her research interest is in nineteenth century Canadian visual and material culture, and her doctoral dissertation is a close study of the floral embroideries found on three historical Canadian quilts. She is a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar, and she was the 2019 Isabel Bader Fellow in Textile Conservation and Research at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre.

Katy Lemay, Illustrator

Katy Lemay’s passion for visual arts dates back several decades. She has a degree in graphic design from Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and has become a well-respected illustrator. While she finds inspiration for her complex collage illustrations in vintage magazines and photos, her ultimate source of ideas is words.

Katy Lemay’s passion for visual arts dates back several decades. She has a degree in graphic design from Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and has become a well-respected illustrator. While she finds inspiration for her complex collage illustrations in vintage magazines and photos, her ultimate source of ideas is words.

https://www.musee-mccord-stewart.ca/en/blog/an-unforgiving-art/

Copied

Error

Copied

Error

Share this content