Permanent exhibition

Until June 27, 2021

Wearing Our Identity – The First Peoples Collection

This exhibition has ended.

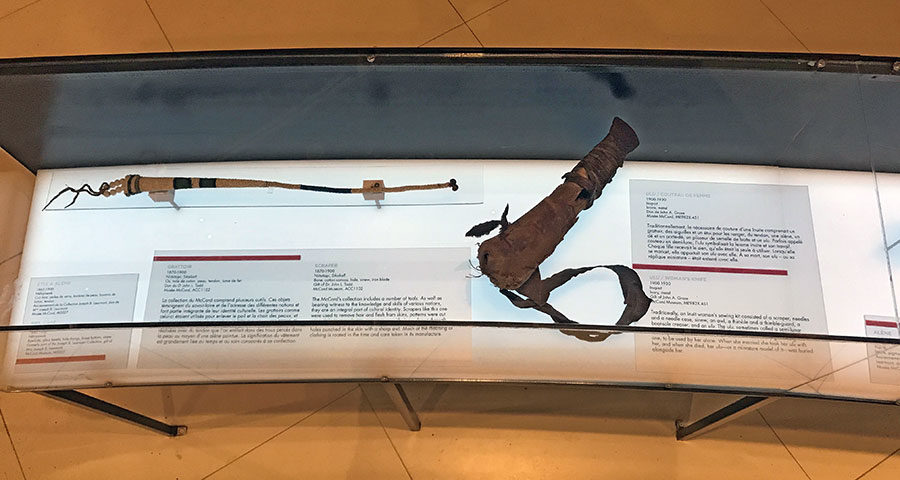

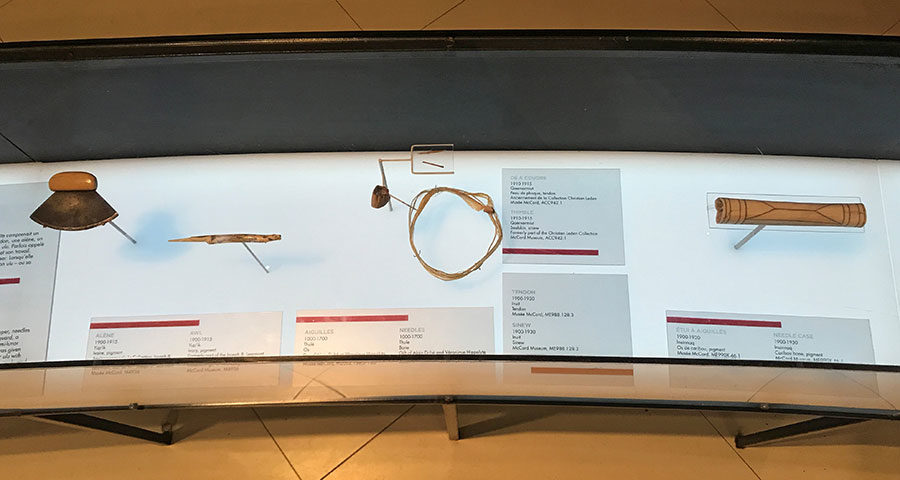

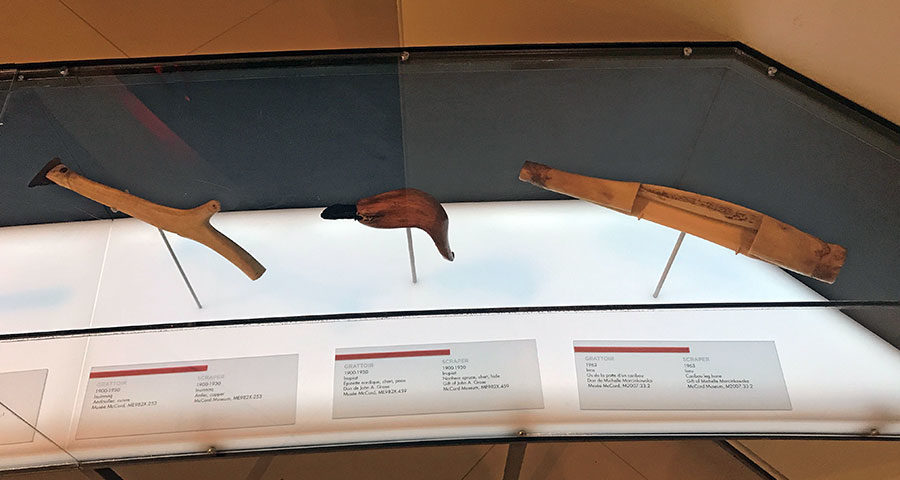

Through some 100 garments and accessories dating from the late 19th century to today, Wearing our Identity – The First Peoples Collection invites the public to discover the importance of clothing in the development, preservation and communication of the social, cultural, political and spiritual identities of the First Nations, Inuit and Métis of Canada.

The relationship between dress and identity is profound for members of Indigenous communities. Beyond its practical use, clothing conveys information about the identity of the individual wearing it and sometimes pays tribute to a person’s significant achievements or highlights the intimate connection between human beings and nature.

Today, clothing eloquently shows the vitality and creativity of contemporary Indigenous cultures, which have found a balance between ancestral knowledge and lived reality, between tradition and innovation.

Produced in close collaboration with an Indigenous advisory committee, Wearing our Identity – The First Peoples Collection is a universal invitation to reflect on the perception of clothing as an affirmation of one’s identity.

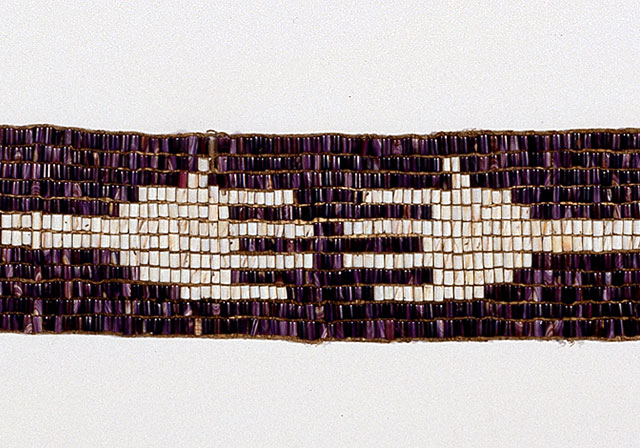

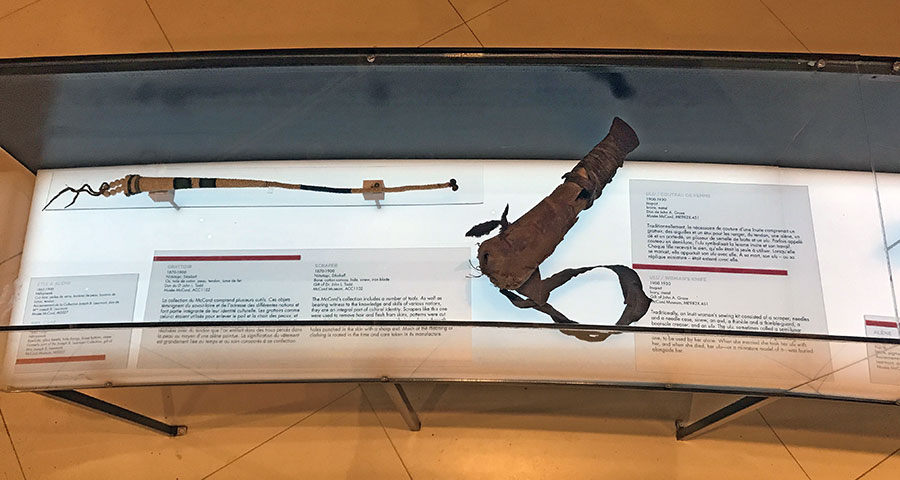

Bandolier Bag

Fashioned exclusively from European materials and adorned with thousands of beads, bandolier bags were primarily for show, as a symbol of identity, wealth, and status. Sometimes called “friendship bags,” they were often created as gifts to strengthen relationships within communities or between nations. Both men and women wore them, usually at ceremonies and celebrations. The wearing of more than one bag was generally the prerogative of a leader or a person of high honour.

Mother’s amauti

Inuit clothing tells the knowledgeable onlooker what Arctic region the person comes from, as well as the wearer’s sex, age, and often, for women, marital status. Important indicators are the size and shape of the amaut (baby pouch), the length and the outline of its lower edge, and the decorative inserts. Traditionally, the infant nestled against the mother’s bare back in the amaut until two or three years of age.

Coat

Coats similar to the one featured in the gallery frequently appear in early photographs of Métis and Dene man. They clearly reflect Indigenous exposure to foreign materials and styles, yet in their essence, they remain traditional: in their function, fabrication, and decoration, there is an evident continuity with the past. To the women who made them and the men who wore them, these coats represents a determination to maintain a separate identity and to preserve cultural values.

Pigment Bag

This small pouch was used to carry red pigment for the face and body, a colour often associated with war. The bag featured in the gallery was taken from a Nêhiyawak warrior who fought alongside the Métis at the Battle of Batoche, during the North-West Rebellion of 1885. It is a telling reminder of the many struggles of First Nations, Inuit and Métis to protect their rights, their land and their survival as distinct peoples.

Nadia Myre

The exhibition also features three works by Nadia Myre, a contemporary artist and member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg Nation, who shares her perspective on identity, resilience and belonging.

Rethinking Anthem, Portrait in Motion and A Casual Reconstruction, Remix, challenge us to question our conception of Canada as homeland, colonial nation and “Native land” from the viewpoint of contemporary Indigenous identity. She plunges us into the heart of a paradigm shift, sometimes making us play the role of the “white man,” sometimes that of the “Native.”

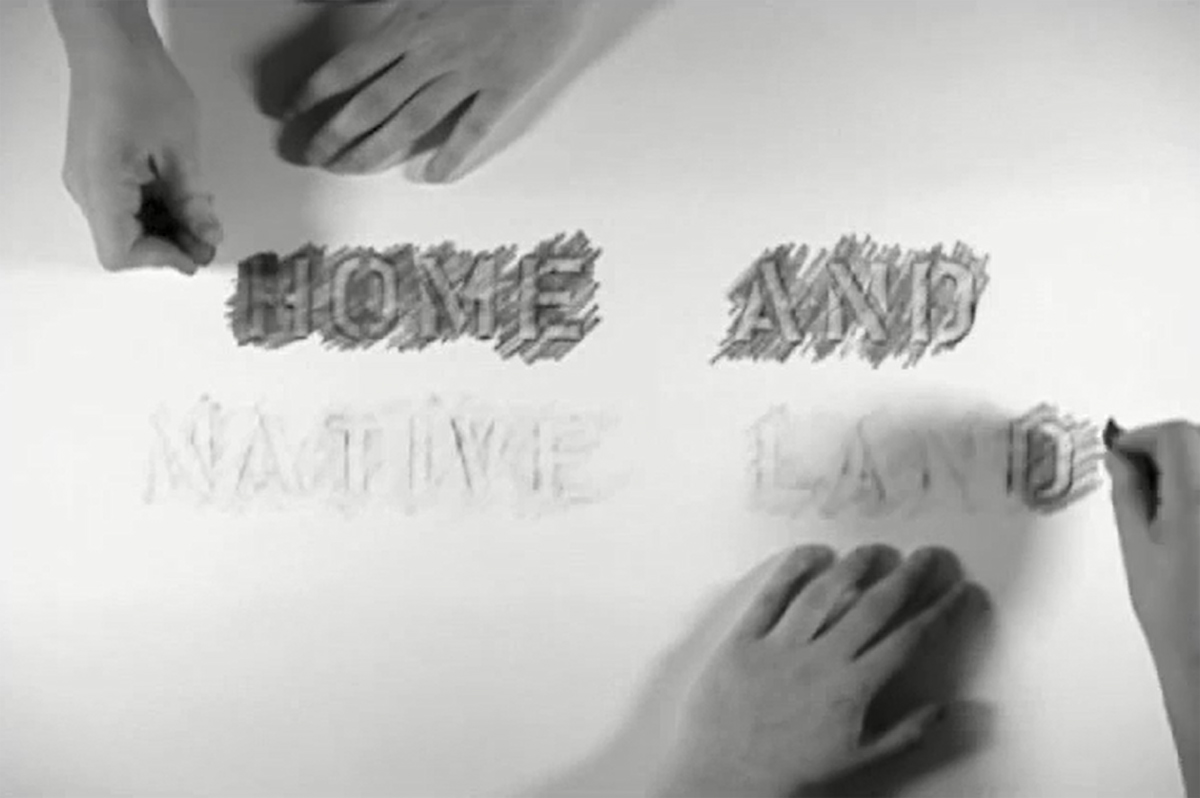

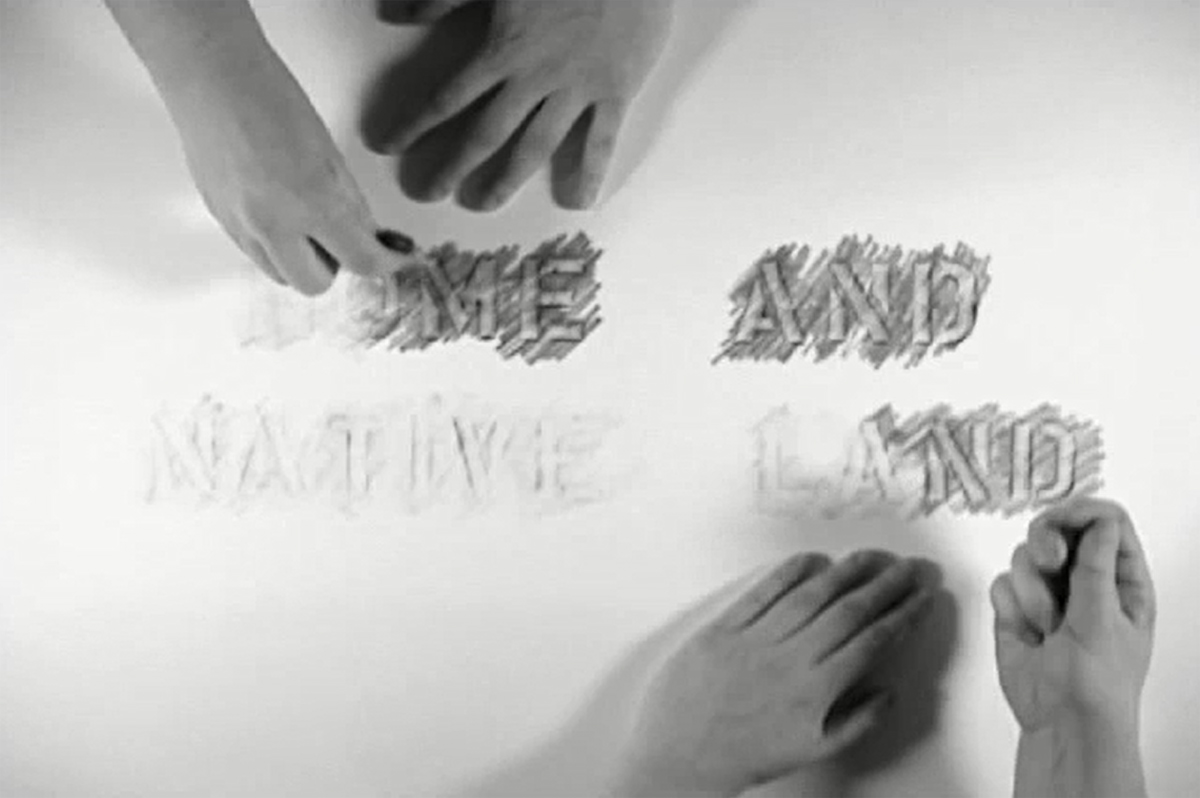

Rethinking Anthem

Extracting words charged with patriotism from “O Canada,” the Canadian national anthem, Myre asks the spectator to engage with the violence of Canada’s origins. By showing two pairs of hands simultaneously erasing the words “HOME AND” while re-inscribing the words “NATIVE LAND,” Myre reenacts a cycle of denial and affirmation, of protest and realization around issues of territory and displacement, home and hospitality, nationalism and native identity, calling on us all to remember that “Canada” is a guest on many unceded Indigenous territories.

Portrait in Motion

Navigating through morning fog, the artist confidently paddles a canoe into the foreground. Portrait in Motion is an allegorical layering that transposes and conflates the exoticized image of “the Native” and the coded representation of the pioneer. As Nadia Myre advances through the fog towards the camera, she blurs the roles of observer and observed, challenging the ethnographic perspective that frames origin stories of Canada as a colonial nation.

A Casual Reconstruction, Remix

In this 10-minute video montage, Myre juxtaposes a dinner conversation with a group of Indigenous friends and a reading of the same conversation by non-Indigenous people. A Casual Reconstruction, Remix interrogates dialogic and documentary formats and notions of authenticity, while examining themes of identity and belonging in relation to Canada’s historical practice of forced assimilation.

Identity Concept

The exhibition offers fascinating insights from people of various Indigenous communities, including Joséphine Bacon, Innu poet; Tammy Beauvais, Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) fashion designer; Stanley Vollant, Innu surgeon; Nakuset, Nêhithawak (Woodland Cree), Executive Director of the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal; and Pakesso Mukash, Eeyou (Eastern Cree) and Abenaki musician.

Learn more about Eeyou musician Pakesso Mukash and about his vision of the notion of identity. Testimony filmed in 2013.

Learn more about Innu poet Joséphine Bacon and about her vision of the notion of identity. Testimony filmed in 2013.

Preventive measures

The Museum staff is ready to offer a safe, pleasant, entertaining experience to all Montrealers!

Learn moreBe an insider!

Subscribe to our newsletter to get the inside scoop on upcoming exhibitions and cultural events.

Subscribe nowOnline Tickets

Reserve a ticket ahead of time to visit current exhibitions and take part in activities.

Tickets